In this part of The Trial of Henry Kissinger, author Christopher Hitchens recounts the destruction wrought on Cyprus in the 1970s.

It is worth emphasizing that Makarios was invited to Washington in the first place, as elected and legal president of Cyprus, by Senator J. William Fulbright of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and by his counterpart Congressman Thomas Morgan, chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

William Fulbright

Credit for this invitation belongs to the above-mentioned Elias Demetracopoulos, who had long warned of the coup and who was a friend of Fulbright. He it was who conveyed the invitation to Makarios, who was by then in London meeting the British Foreign Secretary.

This initiative crowned a series of anti-junta activities by this guerrilla journalist and one-man band, who had already profoundly irritated Kissinger and become a special object of his spite.

Elias Demetracopoulos

At the very last moment, and with very poor grace, Kissinger was compelled to announce that he was receiving Makarios in his presidential and not his episcopal capacity. Since Kissinger himself tells us that he had always known or assumed that another outbreak of violence in Cyprus would trigger a Turkish military intervention, we can assume in our turn that he was not surprised when such an intervention came.

Nor does he seem to have been very much disconcerted. While the Greek junta remained in power, his efforts were principally directed to shielding it from retaliation. He was opposed to the return of Makarios to the island, and strongly opposed to Turkish or British use of force (Britain being a guarantor power with a treaty obligation and troops in place on Cyprus) to undo the Greek coup.

This same counsel of inertia or inaction-amply testified to in his own memoirs as well as in everyone else's-translated later into equally strict and repeated admonitions against any measures to block a Turkish invasion.

Sir Tom McNally, then the chief political advisor to Britain's then Foreign Secretary and future prime minister, James Callaghan, has since disclosed that Kissinger "vetoed" at least one British military action to preempt a Turkish landing. But that was after the Greek colonels had collapsed, and democracy had been restored to Athens.

There was no longer a client regime to protect. This may seem paradoxical, but the long-standing sympathy for a partition of Cyprus, repeatedly expressed by the State and Defense departments, make it seem much less so. The demographic composition of the island (82 percent Greek to 18 percent Turkish) made it more logical for the partition to be imposed by Greece.

But a second-best was to have it imposed by Turkey. And, once Turkey had conducted two brutal invasions and occupied almost 40 percent of Cypriot territory, Kissinger exerted himself very strongly indeed to protect Ankara from any congressional reprisal for this outright violation of international law, and promiscuous and illegal misuse of US weaponry.

He became so pro-Turkish, indeed, that it was as if he had never heard of the Greek colonels. (Though his expressed dislike of the returned Greek democratic leaders supplied an occasional reminder.) Not all the elements of this partitionist policy can be charged to Kissinger personally; he inherited the Greek junta and the official dislike of Makarios.

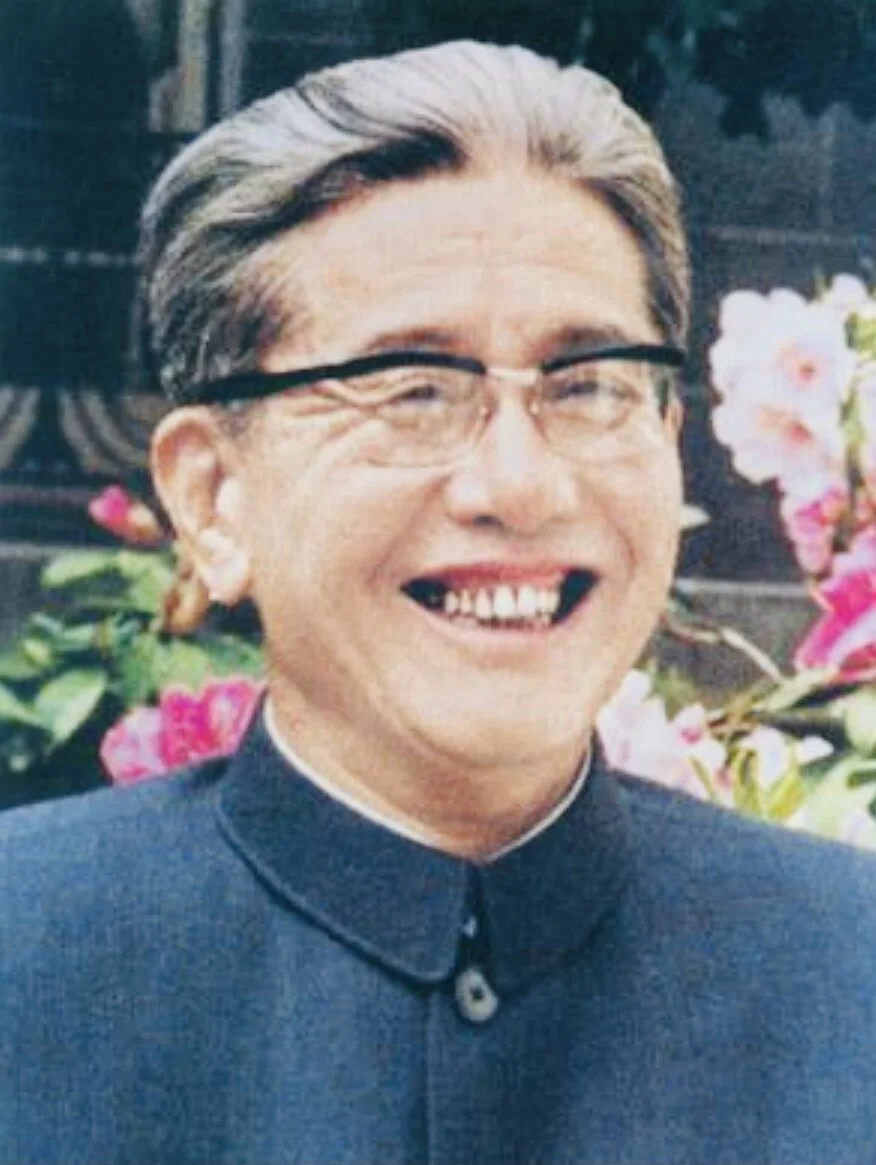

Makarios

However, even in the dank obfuscatory prose of his own memoirs, he does admit what can otherwise be concluded from independent sources. Using covert channels, and short-circuiting the democratic process in his own country, he made himself an accomplice in a plan of political assassination which, when it went awry, led to the deaths of thousands of civilians, the violent uprooting of almost 200,000 refugees, and the creation of an unjust and unstable amputation of Cyprus which constitutes a serious threat to peace a full quarter-century later.

1. To make so confused or opaque as to be difficult to perceive or understand: "A great effort was made... to obscure or obfuscate the truth".

His attempts to keep the record sealed are significant in themselves; when the relevant files are opened they will form part of the longer bill of indictment. On 10 July 1976, the European Commission on Human Rights adopted a report, prepared by eighteen distinguished jurists and chaired by Professor J.E.S. Fawcett, resulting from a year's research into the consequences of the Turkish invasion.

It found that the Turkish army had engaged in the deliberate killing of civilians, in the execution of prisoners, in the torture and ill-treatment of detainees, in the arbitrary collective punishment and mass detention of civilians, and in systematic and unpunished acts of rape, torture, and looting.

A large number of "disappeared" persons, both prisoners of war and civilians, are still “missing" from this period. They include a dozen holders of United States passports, which is evidence in itself of an indiscriminate strategy, when conducted by an army dependent on US aid and materiel.

Perhaps it was a reluctance to accept his responsibility for these outrages, as well as his responsibility for the original Sampson coup, that led Kissinger to tell a bizarre sequence of lies to his new friends the Chinese.

Qiao Guanhua

On 2 October 1974, he held a high-level meeting in New York with Qiao Guanhua, Vice Foreign Minister of the People's Republic. It was the first substantive Sino-American meeting since the visit of Deng Xiaoping, and the first order of business was Cyprus.

Qiao Guanhua

The memorandum, which is headed

"TOP SECRET/SENSITIVE/EXCLUSIVELY EYES ONLY,"

has Kissinger first rejecting China's public claim that he had helped engineer the removal of Makarios.

"We did not. We did not oppose Makarios." (This claim is directly belied by his own memoirs.) He says, “When the coup occurred I was in Moscow," which he was not. He says, “my people did not take these intelligence reports [concerning an impending coup] seriously," even though they had.

He says that neither did Makarios take them seriously, even though Makarios had gone public in a denunciation of the Athens junta for its coup plans. Kissinger then makes the amazing claim: "We knew the Soviets had told the Turks to invade," which would make this the first Soviet-instigated invasion to be conducted by a NATO army and paid for with US aid.