Facing and cogitating these consequences himself, General Telford Taylor took issue with another United States officer, Colonel William Corson, who had written that "Regardless of the outcome of... the My Lai courts-martial and other legal actions, the point remains that American judgment as to the effective prosecution of the war was faulty from beginning to end and that the atrocities, alleged or otherwise, are a result of failure of judgment, not criminal behavior."

General Telford Taylor

To this Telford responded thus: Colonel Corson overlooks, I fear, that negligent homicide is generally a crime of bad judgment rather than evil intent.

Perhaps he is right in the strictly causal sense that if there had been no failure of judgment, the occasion for criminal conduct would not have arisen.

The Germans in occupied Europe made gross errors of judgment which no doubt created the conditions in which the slaughter of the inhabitants of Klissura [a Greek village annihilated during the Occupation] occurred, but that did not make the killings any the less criminal.

Referring this question to the chain of command in the field, General Taylor noted further that the senior officer corps had been: more or less constantly in Vietnam, and splendidly equipped with helicopters and other aircraft, which gave them a degree of mobility unprecedented in earlier wars, and consequently endowed them with every opportunity to keep the course of the fighting and its consequences under close and constant observation.

Communications were generally rapid and efficient, so that the flow of information and orders was unimpeded. These circumstances are in sharp contrast to those that confronted General Yamashita in 1944 and 1945, with his troops reeling back in disarray before the oncoming American military powerhouse.

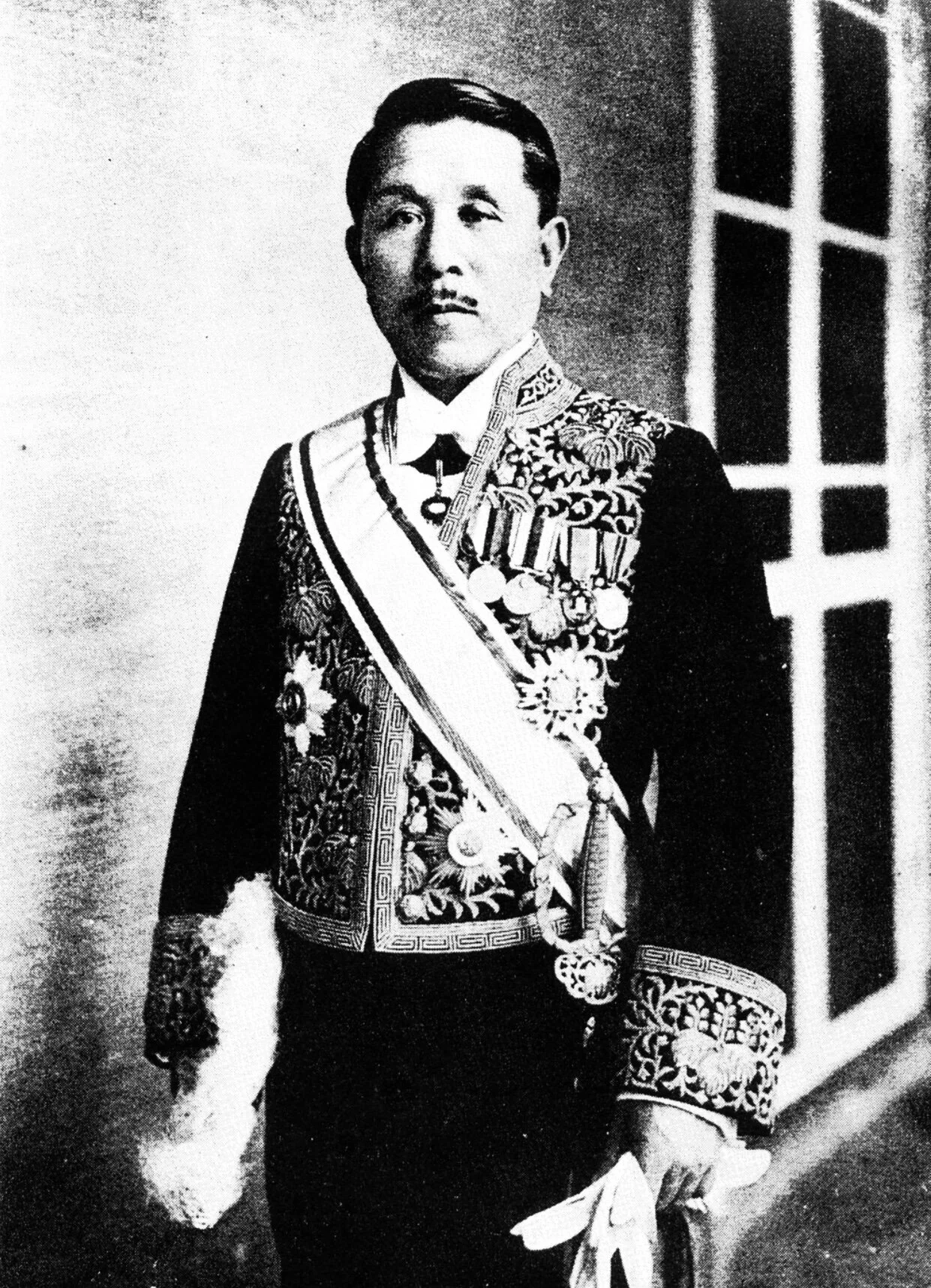

General Yamashita

For failure to control his troops so as to prevent the atrocities they committed, Brigadier Generals Egbert F. Bullene and Morris Handwerk and Major Generals James A. Lester, Leo Donovan and Russel B. Reynolds found him guilty of violating the laws of war and sentenced him to death by hanging.

Nor did General Taylor omit the crucial link between the military command and its political supervision; this was again a much closer and more immediate relation in the American-Vietnamese instance than in the Japanese-Filipino one, as the regular contact between, say, General Creighton Abrams and Henry Kissinger makes clear:

How much the President and his close advisers in the White House, Pentagon and Foggy Bottom knew about the volume and cause of civilian casualties in Vietnam, and the physical devastation of the countryside, is speculative.

Something was known, for the late John Naughton (then Assistant Secretary of Defense) returned from the White House one day in 1967 with the message that "We seem to be proceeding on the assumption that the way to eradicate the Vietcong is to destroy all the village structures, defoliate all the jungles, and then cover the entire surface of South Vietnam with asphalt."

This remark had been reported (by Townsend Hoopes, a political antagonist of General Taylor) before that metaphor had been extended into two new countries, Laos and Cambodia, without a declaration of war, a notification to Congress or a warning to civilians to evacuate. But Taylor anticipated the Kissinger case in many ways when he recalled the trial of the Japanese statesman Koki Hirota:

who served briefly as Prime Minister and for several years as Foreign Minister between 1933 and May 1938, after which he held no office whatever.

Koki Hirota

The so-called "Rape of Nanking" by Japanese forces occurred during the winter of 1937-38, when Hirota was Foreign Minister.

Upon receiving early reports of the atrocities, he demanded and received assurances from the War Ministry that they would be stopped. But they continued, and the Tokyo tribunal found Hirota guilty because he was “derelict in his duty in not insisting before the Cabinet that immediate action be taken to put an end to the atrocities," and "was content to rely on assurances which he knew were not being implemented."

On this basis, coupled with his conviction on the aggressive war charge, Hirota was sentenced to be hanged. Melvin Laird, as Secretary of Defense during the first Nixon administration, was queasy enough about the early bombings of Cambodia, and dubious enough about the legality or prudence of the intervention, to send a memo to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, asking, "Are steps being taken, on a continuing basis, to minimize the risk of striking Cambodian peoples and structures? If so, what are the steps? Are we reasonably sure such steps are effective?"

Koki Hirota

There is no evidence of Henry Kissinger, as National Security Advisor or Secretary of State, ever seeking even such modest assurances. Indeed, there is much evidence of his deceiving Congress about the true extent to which such assurances as were offered were deliberately false.

Robert McNamara

Others involved, like Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy and William Colby, have since offered varieties of apology or contrition or at least explanation: Henry Kissinger never.

General Taylor described the practice of air strikes against hamlets suspected of "harboring" Vietnamese guerrillas as "flagrant violations of the Geneva Convention on Civilian Protection, which prohibits 'collective penalties' and 'reprisals against protected persons' and equally in violation of the Rules of Land Warfare."

He was writing before this atrocious precedent had been extended to "reprisal raids" that treated two whole countries-Laos and Cambodia-as if they were disposable hamlets.